The hike I had planned to do at Kalika Beach, the Sandvikstein, proved to be a lot more challenging than I expected. I took it on anti-clockwise and the first half climbs over lots of bare rock with magnificent vistas, before descending after three kilometres or so, through pine forest to the coast. The return along the coast meant plenty of steep ups and downs, including several with fixed chains in the rock.

I had met a guy with a young medium sized German pinscher who told me there was one place I would need to lift the dog. I’ve put the image of that part below. It was a section with via-ferrata style iron rungs in the rock.

It was all very much fun, and a really good test of the hip. Roja does remarkably well on these sections, considering he isn’t as nimble as he used to be.

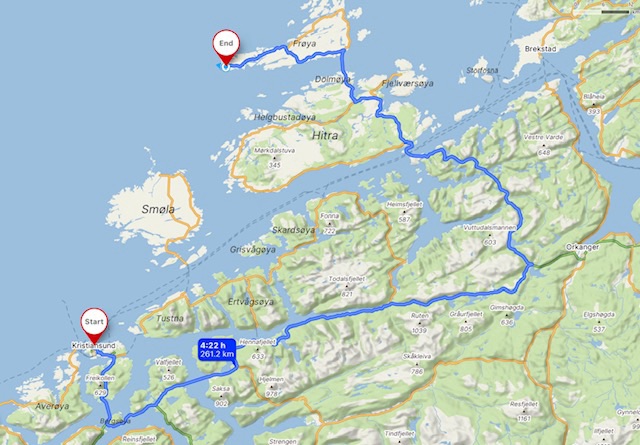

Originally I had planned to stop midway along the journey I had planned up to Frøya island. With a ferry it was about three hours, about twice as much as I like to drive. But, I am keen to stay put in a place for a few nights rather than move on each morning, so I opted for the longer journey. The weather is set fair for the next couple of weeks, so it wasn’t a question of making the most of one particular fine day.

So we are on the island of Frøya, which is linked to the island of Hitra, and in turn to the mainland, by two 7 kilometre tunnels. I had researched a place to stay, near to a hiking trail, but on closer investigation, I opted to go to the small town on the far west of the island, Titran. The town has quite a history, and isn’t as developed for tourism or second homes as other islands. The hotel and tavern at the quay have closed down, and several houses look derelict. There are a few smartly renovated places, but much less than elsewhere. It’s a cloudless evening, and the panoramic views are quite spectacular. I’m parked up at Stabben fort.

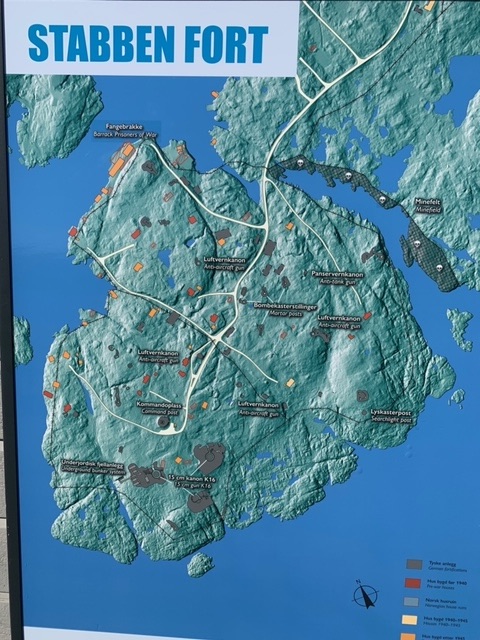

In the spring of 1941, a coastal fort was constructed here by the German occupation forces. Houses and properties were seized or demolished, and many families were forced to abandon their homes, in most cases, never to return.

Stabben was then sealed off using minefields and barbed wire fences.

The main artillery was ready in July 1941, consisting of three 15 cm guns with a range of 22 km. The Stabben fort housed 100-120 artillerymen and a garrison of 100 infantry soldiers.

The fort was developed in stages. In 1942, around 150 Soviet and Yugoslav prisoners of war were brought to Stabben for labour. The prisoners lived in basic concrete huts by the ocean, and were poorly fed and dressed. Three of the many POWs who died at Stabben were buried at the Titran cemetery. In October 1944, Stabben was speedily closed down and its guns moved to Skardsoya in Nordmore. The fort was part of the Atlantic Wall, a 5,000 km network of German fortifications along the coastline from Biscay to Kirkenes.

Another dominant feature of the landscape is the Settringen Lighthouse, which is Norway’s tallest, at 46 meters. The cast iron structure was completed in 1923, a few months after 140 fishermen died in the tragic Titran disaster. In 1851, the lighthouse commission had proposed placing a coastal beacon outside the fishing village. Pressure from fishermen, pilots, captains and local politicians led to the construction of a small lighthouse at Slettringen in 1899. The light cone swept across the water from 20 meters up. Following the Titran disaster many blamed the lighthouse for the high number of casualties. After investigations, the lighthouse director determined that a 50-meter tower would be necessary, and Parliament approved the funding.

The light was manned until 1993, when it became automated. It was granted protected landmark status in 2000.

Just after arrival we took an hour or so to explore the area, but will look more closely tomorrow.

Leave a comment