These days Crews’s influence on storytelling is more widely acknowledged than when he was alive. It may seem surprising for a middle aged white man whose work is fraught with racism and a masculinity so toxic it sometime bypasses misogyny and goes straight into violence.

During his life (1935-2012) Crews witnessed the South’s shift from a rural society to a cosmopolitan one marked by the civil rights movement. Along with that views on Southern literature have changed also. O’Connor, Welty, Caldwell, McCullers, once seen as eccentric outsiders are now revered as writers reflecting diversity. Crews writing is now seen as genuine, almost a part of history that may not generate pride, but at least is honest.

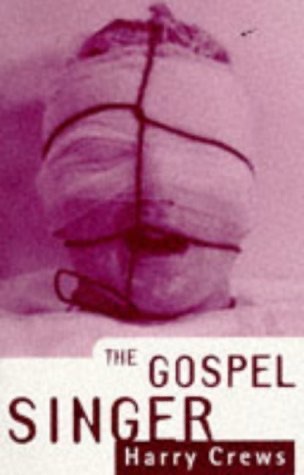

Typically Crews, here we have a travelling freak show, pigs roaming around the interior of homes, and broken countryfolk with huge heads, skin disease and missing legs.

The Gospel Singer, a man with a beautiful voice, rumoured to be able to heal the sick, but actually a sex addict, is reluctantly returning to his socially deprived home town, Enigma. He is followed, always, by a Freak Fair, run by a man called Foot, due to his one 27 inch foot, though he may be the sanest character in the novel.

It begins in a jail cell, where Willalee Bookatee Hull, an African American and preacher, is being held for the rape and murder of the Gospel Singer’s supposed bride to be, Mary-Bell Carter, who has been stabbed 61 times with an ice pick.

This is a chaotic and violent novel, and all the better for it. Crews’s writing is so spiky and precise that the images it conjures up are some you’d rather not see. He wrestles with issues of race, gender, religion and class then stretches them to breaking point. This is a great example of his work, the masses that have assembled to be saved by the Gospel Singer are whipped into such a state of frenzy the novel seems to be headed for one hell of a finale. And Crews delivers.

Here’s a clip as we first meet the famous songster..

The Cadillac was vast, domed, vaulted and trussed, specially built by Detroit to the Gospel Singer’s own specifications, but costing as much as Detroit cared to make it cost, expense being no consideration with the Gospel Singer because he consistently made more money during any given year than he was able to spend. The interior was deep savage red: the seats and headliner formed in heavy leather; the floor padded in spongy carpet. A pale mauve light-indirect, as though emanating from the passengers themselves-lit up the Gospel Singer in the back seat where he lolled, long-jointed and beautiful under his incredible head of yellow girl’s hair, and lit up Didymus-manager, chauffeur and confessor to the Gospel Singer-where he sat, narrow-faced and nicotine-stained, rigid in his dark blue businessman’s suit. He turned to look over his shoulder at the Gospel Singer, his mouth like the blade of a hatchet. He wore a clerical collar.

My GoodReads score 5 / 5

Leave a comment